How I learned to stop worrying and love invasive species

Or, Novel Ecosystems in an Ambivalent Nation

This post is based on a paper I presented at the International Australian Studies Association Conference 2025, as pictured below.

Last year, an article caught my eye. Its headline was written in the typically verbose style of The Conversation: ‘The greater stick-nest rat almost went extinct. Now it’s found an unlikely ally: one of Australia’s worst weeds.’1

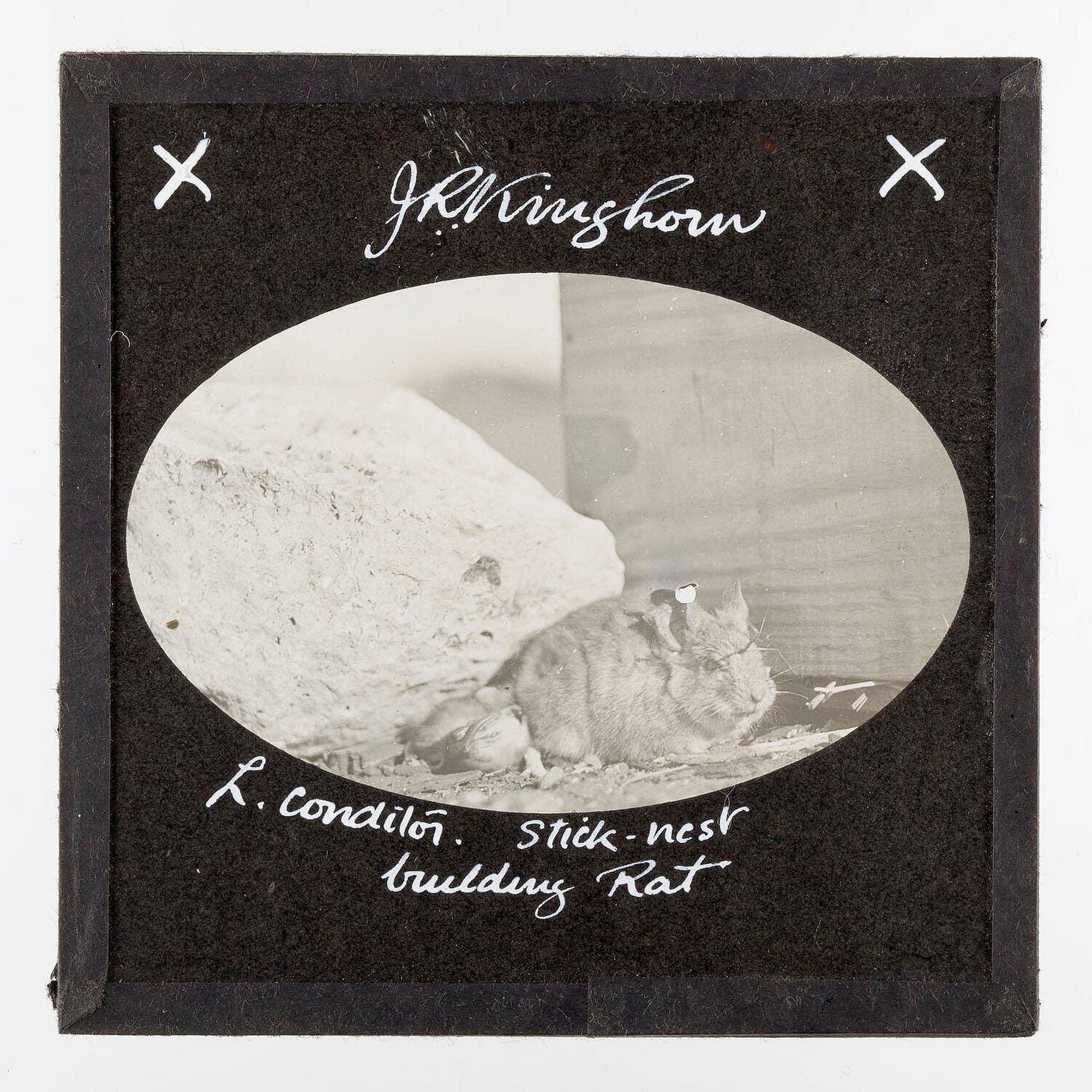

These stick-nest rats are remarkable animals, as the authors of this article explain.2[2] As you can see here, they’re utterly adorable. And as the name suggests, these native rodents do indeed build nests out of sticks; for this reason, the species has also been called the ‘housebuilding rat’. But an awkward and prosaic term like ‘stick-nest’ does an injustice to these edifices, which are as robust and sophisticated as any beaver’s dam or badger’s sett. The nests ‘can be a metre high and 1.5 metres wide’; they are shared by matriarchal clans of rats for generation after generation. They are constructed with various entrances, chambers and passageways — Charles Sturt compared them to beehives — furnished with soft grass. The rats gather up twigs and leaves, carrying them in their prehensile tails, then glue them together with a sticky, cement-like, preservative substance known as ‘amberat’, which is — cue winces and groans — the product of the rats’ urine and faeces. Gross as it may seem, amberat makes the nests astoundingly durable: when left under a rocky overhang or in a cave, they can endure intact for a millennium or more.

The ecological changes unleashed by colonisation imperilled the greater stick-nest rat, like so many other native mammals.3 Though the species was once found in arid landscapes from Shark Bay to the Darling River, they were wiped off the mainland, with only a small remnant remaining in the Franklin Islands, off the South Australian coast near Ceduna. While the authors of this article cite predation from cats and foxes — that old chestnut! — as the sole cause of the rats’ decline, older sources quite rightly admit the truth is less clear. Certainly, cats and foxes must have taken their toll, but so did competition from rabbits and, perhaps most of all, the destruction of habitat by settler pastoralists and their livestock.4

This little, lingering population has proved resilient, however. Over the last few decades, conservationists have translocated individuals from the Franklin Islands to seed new populations on other islands and in ‘feral predator-free’ reserves on the mainland.5[5]

The authors of this article studied a population of stick-nest rats on Reevesby Island in the Spencer Gulf. ‘To our surprise,’ they write, ‘we found these rats seemed most at home amongst African boxthorn, an invasive weed of national significance.’ Boxthorn is a large, thorny shrub. The authors describe its negative impacts thus: ‘it disrupts livestock movements, blocks access to water sources and takes over land’. Though boxthorn may indeed be a problem for humans, sheep and cattle, it’s clear that it’s been a boon for the stick-nest rats on Reevesby Island. Boxthorn thickets make for safe places in which the rats can construct their nests. Moreover, the authors found that boxthorn accounts for ‘just over half of the stick nest rat’s diet on the island, despite making up only a tenth of the available vegetation’. Concluding, the authors warn that boxthorn may still need to be eradicated, that it may still go on to cause ‘ecological collapse’ on Reevesby Island at some hazy and hypothetical future date.

As I have explored elsewhere, when settler Australians make distinctions between native and non-native nature, they are usually saying something simultaneously about Australian society, intentionally or otherwise. For much of the nineteenth century, introduced species were associated with settlers, sometimes even referred to as ‘colonists’, their presence in Australia seen as a force for and an indicator of civilisation. Towards the end of that century, settler nationalism grew into a significant political current, and settlers came to see themselves as the rightful inheritors and possessors of the continent – the new ‘natives’. Thus, introduced species gradually came to be disdained as ‘foreigners’, associated in turn with non-white immigrants and conceived of as intrinsically threatening to established ‘natives’. Though it has waxed and waned somewhat over the decades, this latter set of associations remains current: settler Australians and First Nations people alike tend to identify with native flora and fauna and see non-natives as unwelcome or, indeed, malevolent newcomers.6

Which leads me back to this story about the boxthorn and the stick-nest rat. Now, if we strip away all the stuff about ‘native’ and ‘invasive’ here, the story basically boils down to a much simpler headline: ‘Rat eats shrub’. But ‘rat eats shrub’ doesn’t win you grant money, doesn’t get your papers published, doesn’t get you interviewed by the ABC and Australian Geographic. To be clear, I’m not accusing these authors of being self-interested careerists — I’m not even trying to be cynical about academia in general — I’m just saying that even in the supposedly rigorous and objective realm of science, people still use nature to tell stories about human society.

My reading of the story these ecologists are telling is this: immigrants can be accepted, as long as they help natives; the newcomer has to provide some benefit to the established resident. If they prove, instead, to be problematic, then immigrants must be eliminated.

This narrative can map onto human politics in different ways. Many of us would find this notion callous — at best — if applied to, say, non-white asylum seekers. But if a radical Aboriginal activist applied this same logic to white settlers, well, then we might find ourselves nodding along in agreement.

Again, to be absolutely clear, I’m sure if you asked these ecologists their views on immigration and settler colonialism and the state of Australia in general, they would say nothing of the sort. They’re not telling this story on purpose — at least, I certainly don’t think so. But this seemingly empirical, factual description of the interactions between a mammal and a shrub on a tiny island necessarily resonates much more broadly in our minds, ringing little bells attached to everything else we hear about ‘natives’ and ‘invaders’; whether the authors intend it or not, it speaks to wider and deeper anxieties, hopes, desires — to the values and sentiments that underpin our society.

Here's the thing, though. ‘Native’ and ‘invasive’ are not really-existing types of life; they’re not qualities that inherently reside in certain species, like genetic code. Rather, they’re concepts that humans impose upon nature. It’s all fake. We made it up.7 So we’re free to imagine nature differently, if we want to.

As this article suggests, the story of the stick-nest rat and the African boxthorn is just one instance of a much broader pattern. Other research has shown that boxthorn is also favoured shelter for wombats, little penguins and (critically endangered) orange-bellied parrots, and a variety of native birds and small mammals eat its leaves and fruit.8[8] This presumably benefits the boxthorn too: the waste and excrement of animals living at its roots help the plant grow, and the animals that eat its fruit play a vital role in spreading the plant’s seeds. Furthermore, the much despised, non-native weeds blackberry and lantana also provide food and habitat for native wildlife including ‘bandicoots, blue wrens, antechinuses and bush rats’. While the authors’ statements about African boxthorn are extremely cautious — dare I say paranoid? — it’s clear that non-native plants and native animals often get along. Perhaps, then, the old dichotomy of good natives versus bad invaders is no longer useful (if, indeed, it ever was). Perhaps we can afford to envision ecology in less stark terms.

I admit, I like reading this kind of story. The landscapes I grew up in — the landscapes that I feel most connected to — are neither purely European nor purely Australian. Fox and possum, sparrow and ibis, blackberry and lillypilly – they all make up what I think of as ‘home’, and I can only imagine the same is true for many people reading this. Increasing numbers of ecologists now recognise and study what they call ‘hybrid’ and ‘novel’ ecosystems, assemblages of species which have recently come into existence due to human activity but which, unlike a farm or a garden, are not reliant on active human intervention for their maintenance.

For much of humanity, well beyond Australia’s shores, these novel ecosystems are the only ones we’ve got. Across the globe, humans have moved animals, plants, fungi, microbes on ships and trucks and aeroplanes, taking them deliberately or accidentally to areas they might never otherwise have reached. This phenomenon, it’s safe to say, gets a lot of bad press. Yet the ecologist Mark Williamson has estimated that only about 0.1% of ‘invaders’ actually prove to be serious pests. 99% simply never establish wild populations in the long term. The remaining 0.9% of successful novel species neatly slot in to pre-existing networks of predation, competition and cooperation.

Meanwhile, the established species usually adapt, just as stick-nest rats have adapted to boxthorn. A 2018 study of southern brown bandicoots in outer Melbourne found they were twice as abundant in roadside vegetation as they were in intensively managed and protected ‘natural areas’. Bandicoots flourished alongside introduced weeds, foxes, cats and black rats — not to mention lawnmowers, cars and chip packets. In habitat that was meant to be more ‘pure’, more ‘natural’, more ‘Australian’, they were struggling. Or think of the cane toad. Since the 1980s, it’s been common to portray this admittedly unpleasant creature as a kind of slow-moving ecological apocalypse, devouring everything in its path like Bart Simpson’s bullfrogs. Yet Rick Shine, who probably knows more about the toad than anyone else ever has or will, has written, ‘No native species have gone extinct as a result of toad invasion’.9 That’s pretty unambiguous. We like to imagine native species as uniquely vulnerable to competition, either especially innocent or especially archaic, but the evidence doesn’t really bear this up.10 Several native predators — rakali, snakes, kites, possibly even the good old purple swamphen — have learned how to eat cane toads without dying from the amphibian’s infamous poison (or simply have an in-built resistance to the toxin). There was no animal like the cane toad in Australia prior to the 1930s. It was a shock to the system. Nevertheless, life, uh, finds a way. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be concerned about the spread of the cane toad. But it does remind us that native ecosystems and native species can adjust to and accommodate newcomers. Not every new arrival must be a catastrophe.

It’s well beyond doubt or denial that colonisation has wreaked havoc upon historical ecosystems in Australia. Much has been lost. It’s right to mourn that. But much remains. Many native species continue to survive and succeed in changed and still-changing landscapes, coexisting with or taking advantage of newcomers. Every time you see a kangaroo lounging on a golf course, a native bee buzzing around roses, a seagull or an ibis or a raven raiding a rubbish bin, you’re seeing the old Australia thrive among the new. That’s an interesting metaphor too. That’s a narrative that might be worth telling. And yet, for the most part, we persist in seeing Australian ecology as a great Manichean struggle between native and invader. This, despite the evidence to the contrary we see all around us in our daily lives. That narrative tightly contains the ways we can understand this continent, its flora and fauna, and its diverse, anxious, fractious humanity.

As finer scholars than I have argued, settler Australians often seem to resort to ecological restoration as a way of proving their connection to the land.11 As in the kind of thinking that says, ‘If I spray these weeds, if I run over this rabbit, if I plant this gum tree, then that shows I really care about Australia.’ It can be a way of saying sorry, too — of trying to make up for the damage caused by colonisation. But this is often a very shallow kind of decolonial work. Imagine a bunch of activist-minded settler volunteers, sacrificing a Sunday to eradicate boxthorn from a local wildlife reserve. Such an act may seem terribly green and altruistic, but given what we know about this plant in Australia, think about what it would really mean. Boxthorn makes it harder to farm sheep and cattle. Settler pastoralism, of course, was what — more than anything else — fuelled the murder and dispossession of Aboriginal people in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Any Australian historian can bring to mind horrific stories of shepherds abducting Aboriginal women; of Aboriginal men shot dead for the crime of spearing a cow; of whole Aboriginal communities reduced to a kind of serfdom on missions and pastoral stations, as late as the 1960s. And this is to say (almost) nothing of the despoliation of the land, the hoofs and the axes, the erosion and the salinification that came next. Boxthorn gets in the way of all this: it prevents settlers from (mis)using Country, from profiting off stolen land. Meanwhile, this same plant demonstrably provides food and shelter for native wildlife, including some highly endangered species. Getting rid of boxthorn, then, suddenly seems like not such a good idea, unless you’re a farmer. If African boxthorn is an invader, it’s an anti-colonial one: a kind of Cyrus figure, if you’ll permit an Old Testament reference, a liberator come from afar to free Aboriginal Country from the settlers’ yoke. Thinking synecdochally, maybe the boxthorn heralds an era of resurgent Black-Blak solidarity – African migrants and First Nations people banding together to fight white supremacy.

Okay, sure, that’s probably a silly way of thinking and writing about a plant with no discernible political allegiances and indeed, of dubious agency in any capacity. The boxthorn itself has no idea about any of this, right? It just wants to live, to grow, maybe to reproduce. But all this is not any sillier than the ways many serious scientists and land managers and, yes, even historians write about ‘invasive species’.

My research has led me to believe that making strong, normative distinctions between native and non-native has had a misleading effect in Australia. Attempts at managing non-native pests have often proven to be futile; the ‘invaders’ also serve as scapegoats, distracting attention away from underlying ecological issues such as land clearing, water theft and climate change. I would like to see us focus on the ecosystem services and the cultural values that species provide, regardless of their origins — and to think, too, about what intrinsic rights organisms might have to live and flourish, even when they annoy or distress us.

The trouble is, we’re stuck with narratives. As much as I want to unpack all this human baggage and see animals and plants ‘as they really are’, I know the best we can do is replace a mean, petty narrative with something more inclusive and generous. So it’s worth asking, if we do downplay the distinctions between native and non-native in ecology, what will that say about human nativeness, human belonging? What are the implications of the stories that I like?

On the one hand, the story of the stick-nest rats and the African boxthorn gives us a potentially utopian vision of native and non-native cooperating. The story suggests, perhaps, that Indigenous people, established settlers and more recent migrants can learn from each other, potentially build an equitable society together, where nobody loses out. But I’m conscious, too, that this vision lets settler Australians off the hook. A naïve reading of non-human nature in this vein might suggest that reconciliation and reparation are unnecessary in the human realm, that we all just need to move on. And as much as I want to defend or at least apologise for non-native species, such organisms were introduced by invading settlers as part of a violent colonial project, and in many ways, they continue to perpetuate that colonial project. I think it’s foolhardy, or even downright sinister, to dream of wiping blackberries and cane toads and boxthorn off the face of the continent — to believe it’s possible or even desirable to return to some imagined state of pre-colonial purity. At the same time, I think it’s deeply important to understand the violence and oppression with which these species are entangled and the deleterious impact they have often had not just on indigenous ecosystems but on Indigenous people and cultures.

So I find myself in a jam — not wanting to reproduce xenophobia nor to downplay the horrors of settler colonialism — not wanting to condemn non-native species nor to absolve them of their coloniality. There are real stakes to all this — real lives, human and non-human, that are shaped by the stories we tell.

But it seems to me that, whether we like it or not, Australia is now, irrevocably, hybrid — ecologically and culturally. Whatever happens afterwards, I know that the first step in the right direction is being honest about that hybridity and accepting it. We might celebrate it or rail against it, but it’s not ever going away.

If you have a question about the plants and animals in your backyard, get in touch! Simply write to simonfarley@substack.com or use the button below. And if you liked this story, please share it with a friend!

What I’ve been watching:

Wallace & Grommit: Vengeance Most Fowl (Nick Park, Merlin Crossingham, 2024)

Trap (M. Night Shyamalan, 2024)

The Wedding Singer (Frank Coraci, 1998)

What I’ve been reading:

The Navigating Fox (Christopher Rowe, 2023)

Dictionary of Fine Distinctions (Eli Burnstein, 2024)

Call for the Dead (John Le Carré, 1961)

That’s not a headline — that’s two whole sentences!

My main source of information on these creatures, apart from the article mentioned in the text, is: Fred Ford, John Gould’s Extinct and Endangered Mammals of Australia, National Library of Australia, 2014.

Indeed, a closely related species — the lesser stick-nest rat — is, sadly, entirely extinct.

I’m here relying on: Derrick Ovington, Australian Endangered Species, Cassell Australia, 1978. Ovington called pastoralism ‘the critical factor’.

Stick-nest rats may well be especially vulnerable to cats and foxes, but I doubt they prefer being eaten by native predators like owls and snakes.

I stress ‘tend to’ as there are so many contradictions and exceptions. To say nothing of the various incoherencies and paradoxes in settler culture, it’s worth pointing out that, while many Indigenous people see introduced organisms as symbolic of colonialism, non-native species have also been incorporated into the lore and kinship networks of many First Nations groups.

Sure, we might have had good reasons for making these categories up — they might be very useful in all sorts of ways — but that doesn’t make them any less fake.

See, e.g., Michael Noble and Robin Adair, ‘African boxthorn (Lycium ferocissimum) and its vertebrate relationships in Australia’, Plant Protection Quarterly 29, no. 3 (2014).

A fuller quotation only underscores the point: ‘…and many native taxa widely imagined to be at risk are not affected, largely as a result of their physiological ability to tolerate toad toxins (e.g., as found in many birds and rodents), as well as the reluctance of many native anuran-eating predators to consume toads, either innately or as a learned response.’

Again, this is rooted in settler colonialism and xenophobia. Just as Indigenous people were expected to ‘fade away’ or ‘go extinct’ in the face of a supposedly more advanced culture — just as white unionists and socialists considered themselves unable to compete with Asian workers, necessitating the White Australia Policy — so too do we see ‘Australian’ organisms as backward and frail. Jack Ashby makes a solid and very accessible version of this argument in his book Platypus Matters (2022).

I believe Ghassan Hage was the first to make this argument at length, in his 1998 book White Nation.

Ahhh! I loved reading this, Simon! Would've been great to see you present it, too, so thank you for sharing it for those of us who weren't at the conference. I'm going to read your latest journal articles now - really excited as I think they will be perfect additions to some of my thesis chapters.

Interesting and insightful as always.

This piece came at an interesting time for me, as I've spent most of today preparing for a Stick-Nest Rat trapping survey. The population we'll be monitoring is really struggling, despite being in a fox and cat free area, apparently due to extreme heat events and drought. Foxes and cats undoubtedly played a role in their decline, but there's so much more to their story. With a changing climate, no ecosystem is going to look exactly as it did in the past, and I think a lot of ecologists, myself included, have yet to properly reckon with that.